Overcoming expert blindness: Unlock MTB skills through peer learning

Discover the untapped benefits of learning side-by-side with your peers

Have you ever found yourself on the trails, feeling frustrated by well-meaning advice from a more experienced rider that just didn't click?

Have you ever been alone with a how-to YouTube video, trying to master an MTB skill, and wondered which crucial steps were left out?

We’ve all been there.

I was delighted to see that

’s first post to his Substack was The Curse of Knowledge: Why experts often fail at teaching beginners.He wrote:

This psychological phenomenon occurs when an expert assumes that others have the background to understand their specialized language and concepts. In cycling, this might manifest when a seasoned rider, mechanic, or industry insider uses technical terms or complex techniques that are second nature to them but utterly confounding to a novice.

Other thought leaders I follow have also noticed the phenomenon. Two examples:

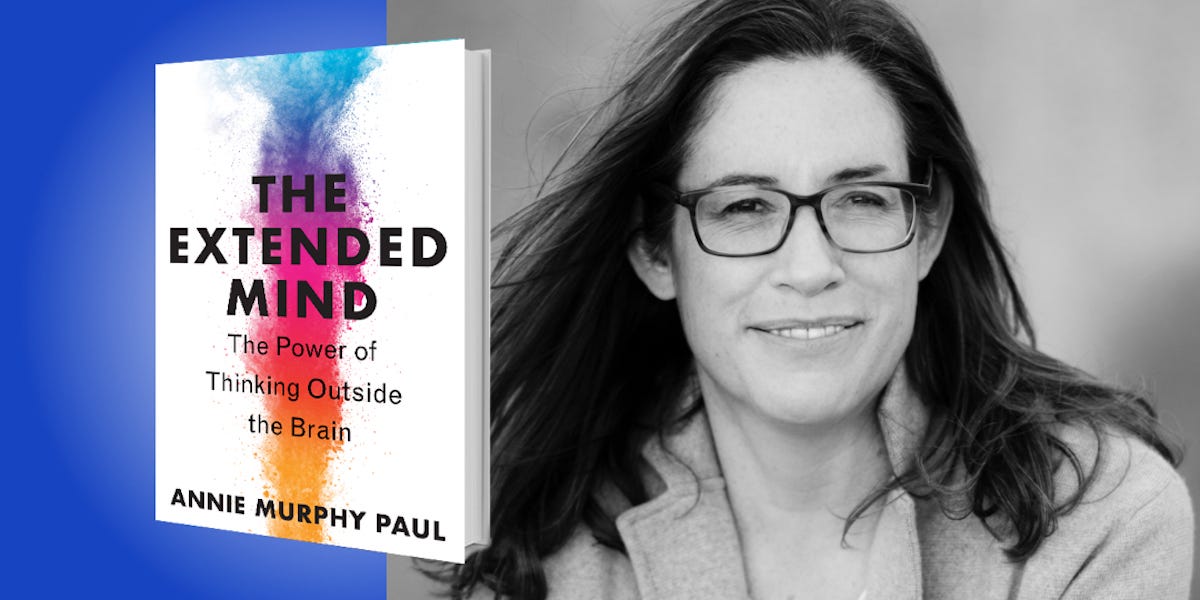

Annie Paul, author of The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain, wrote in a post on X:

"The curse of expertise" refers to the fact that very skilled performers have made their patterns of thought and action so automatic that they can no longer explain them well to beginners. This phenomenon occurs in many realms, including sports.

Trevor Ragan interviewed Harvard Business School Professor Ting Zhan in January about the phenomenon for his Learner Lab podcast: Overcoming the Curse of Expertise: Better Learning & Leadership. Zhan says:

A lot of the work that I've been doing looks at how the curse of expertise impacts the ways in which experts actually can coach or advise or teach novices. And one of the main barriers to this process is experts' ability to retrieve their understanding of how novices are thinking and feeling as they're engaging in this learning process.

The power of peers

Alvo, Paul, Ragan, and Zhan all suggest effective strategies that an expert, leader, or coach can deploy to guide a beginner without succumbing to the curse of expertise.

However, peer learning can also be an effective strategy for dealing with the experts’ curse.

In the book Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning, this paragraph about the curse of knowledge (AKA the curse of expertise) references the power of peers when learning something new:

The better you know something, the more difficult it becomes to teach it. So says physicist and educator Eric Mazur of Harvard. Why? As you get more expert in complex areas, your models in those areas grow more complex, and the component steps that compose them fade into the background of memory (the curse of knowledge)… Mazur says that the person who knows best what a student is struggling with in assimilating new concepts is not the professor, it’s another student.

Here are four advantages of learning from peers that can mitigate the curse of expertise that I’ve gleaned from various sources:

Peers at a similar level of skill acquisition are likely to share similar challenges, mistakes, and misunderstandings. This shared experience can make it easier for them to empathize with each other's struggles, as they are likely encountering or have recently overcome similar obstacles. They can offer each other insights based on fresh, personal experiences.

Learning a new skill can be fraught with frustration and vulnerability. Students may feel more comfortable expressing their difficulties and asking questions among peers equally exposed to the learning process. This sense of psychological safety can encourage more open discussion about challenges, leading to a better understanding of common difficulties and how to overcome them.

Learning alongside peers provides a unique motivational boost. Seeing someone at a similar skill level achieve a breakthrough can be incredibly inspiring, making one's goals seem more attainable. Peer learners often provide encouragement and support in a way that feels more immediate and personal than feedback from an instructor, which can enhance persistence and effort.

The act of teaching or explaining a concept to someone else is a powerful learning tool. When a learner takes on the role of the teacher to help a peer, they reinforce their own understanding and uncover gaps in their knowledge. This reciprocal teaching benefits both the explainer and the learner, promoting deeper understanding and retention of the skill or concept.

How to find peers to learn with at your level

It’s not easy! Here are four ideas that come to mind:

Taking online classes and face-to-face MTB clinics that provide instruction on the same MTB skill for those at the same level can be helpful for peer learning. But you need to make sure that there’s plenty of opportunity for peers to interact with each other without the instructor being too closely involved.

Joining online forums and user groups devoted to a specific MTB skill can help. But most have a mix of people at various skill levels, and it can be challenging to explain your beginner-level problem without the expert-level riders chiming in, oftentimes with their own curse of expertise.

Sessioning obstacles and challenging terrain in a group can often provide the opportunity to engage with others of similar ability levels. See my free Online Challenge mini-course on MTB sessioning for more.

Finding a buddy to ride with or chat online with (or both) who’s either learning the skill simultaneously or who is a step or two ahead or behind can be best, IMHO.

Patrick Mitzel has been my go-to riding/online chat buddy for several years. We live about an hour apart, and we’ve teamed up to help each other improve our skills at wheelies, jumps, and skinnies.

More recently, he’s been helping me to learn pedal kicks. He’s gotten pretty good at it over the past year (his memory of his struggles is still fresh!), whereas I’m a rank beginner. Here’s a clip of Patrick in his driveway about a month ago:

Here’s a 44-second clip of me from my first pedal kick practice session in my garage in early January. Can you guess the hardest part of learning this initial ‘chunk’?

The challenge is keeping the front wheel straight at launch so you don’t tip to one side or the other after triggering the standing wheelie with the initial ratchet motion. I’m good holding a track stand on grass or dirt with the front wheel turned on a slight incline. But I suck at holding a track stand with the front wheel straight on a hard, level surface with my weight over the rear wheel. Of all the pedal kick videos I’ve watched, none mention this as a possible struggle.

Below is a 34-second clip of me practicing pedal kick launches a month later in February. By then, I had figured out some adjustments that helped (engaged core, better hip hinge). These were my three best attempts that day, but I still had several failed launches:

When I told Patrick about it, he validated my frustration, saying he had a similar struggle with his launches when he first started. That felt so good to know.

He then offered a tip for solving the problem of keeping the front wheel pointed straight instead of using a traditional track stand before launch: rocking and hopping in place with the brakes locked.

As an example, he sent me this clip of BICP instructor trainer Travis Brown rocking his trials bike to get positioned for an endo side drop off a platform in Patrick’s driveway during a recent practice session:

I plan to take time out from pedal kick practice to improve at rocking in place. I know I can count on Patrick for feedback.

So yeah: peer learning.

Your turn

Have you encountered the curse of expertise on the trails or in teaching others? How did it affect your learning or teaching experience, and how did you navigate it?

From your experience, what are the standout benefits and potential drawbacks of learning MTB skills alongside peers? Have any particular moments or lessons stuck with you?

Share your stories, and let's learn from each other's experiences.

Sort of.

I do ride-throughs with a few local buddies and, on occasions, ride intensively with my family.

Although we do things up to Black Diamond, we mainly just ride, with very little of the intense learning you are looking at.

Of course we support each other, especially on the more advanced features -- including recon and some coaching, especially of good lines. But it's really focussed on a successful completion of each obstacle, not on learning per se.

My own intense learning is solitary.......I like fooling around in odd moments and in quizzing someone who is pulling a neat trick.

It seems that progress is made, on the whole, by role modeling........and a kind of osmosis......?

..........also I find the video option very useful.

Whew........heavy stuff...

At this level of clinical investigation it may be useful to step back and consider the Sufi story of the Blind Men and the Elephant: everyone's right and everyone's wrong!

As we wrestle with more complex behaviors, it is also useful to standardize our terms -- organize our jargon into a more exact lexicon -- so we all have the same apples and oranges on the table. eg the term "automatic" is a vague popular description of an amazing complex automotive concept, which is easily misunderstood and/or used out of context.

The main elements I see in this large learning area is the difference between "empathy"and "skills/knowledge/expertise.

In my model there is absolutely nothing "wrong" with the Holy Grail of skills/knowledge/empathy/expertise. The Achilles Heel here is the empathy of humans.........and MTB teachers in general. Alas, very few of us seem to be able to really empathize, even with students (what about our children?!). There are so many temptations to grandstand, seek dominance, patronize etc (mansplain?).......

Much of the article has useful ways to enhance empathy (at the risk of "the blind leading the blind?).

The issue of Lack Of Empathy is a complex therapeutical challenge........fortunately made easier and more fun by our love of the outdoors, of a good challenge -- and the traditional after-ride mug of good ale.