MTB skill plateaus are frustrating. Among the strategies to get unstuck: curiosity

It helps to treat your plateaus like a scientist reacts to failed experiments

I know plateaus well. Last July, I authored a post titled, I'm stuck on an MTB boulder plateau. It’s been over a year since I’ve tried to improve my wheelies without much success. Last week I posted on my Instagram how, after a year, I seemed to have gotten past my plateau with slow fakies. Will it stick?

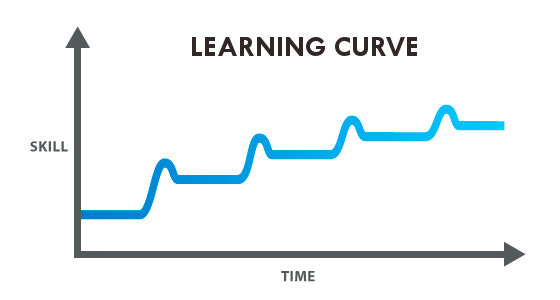

Plateaus are an inevitable stage in learning. Most of the plateau-related graphs I see online look something like this:

But when you’re in the middle of a plateaus, it feels like this:

Name one or two plateaus you're stuck on that you'd like to get beyond, either MTB-related or some other skill. Comment below:

Poll: Frustration level

Plateau Strategies

The following strategies help deal with a plateau:

Getting feedback on your current performance of the skill

Reflecting on each practice session via a written journal

Figuring out what to unlearn

Getting better at creative problem-solving

Reacting to failures and lack of progress with curiosity instead of frustration

Plateau Strategy: Curiosity

I will focus on the last one of the above strategies, "Reacting to failures and lack of progress with curiosity instead of frustration." It's the mindset that's needed before you tackle the others.

Neurologist and musician Dr. Josh Turknett has a YouTube video titled "5 Strategies for Reaching Your Musical Goals." He's speaking about learning to play a musical instrument, but it's 100% applicable to learning a mountain biking skill.

It includes a two-minute segment on Goal #2 that starts at the 5:47 mark titled, "Treat your practice like a scientist."

The transcript of the segment is below.

Transcript: Dr. Josh Turknett on how to treat your practice or your training like a scientist:

So when you're evaluating yourself and evaluating how you're doing, think like a scientist. Imagine that you are given a recording of someone that you don't know, and your only job is to listen and evaluate how they're doing and what sorts of things that you think they need to work on to move them forward.

So all that really matters is understanding where you are now and where you need to go next. If you're a scientist collecting data, data is neither good or bad. It's not about making a value judgment. It's just about accurately assessing the state of affairs right now and using that to determine the next best step for moving forward.

Everyone who is learning anything is on different points along the learning timeline. Just like children who are learning to walk or talk. We don't say that a one-year-old child is a bad walker because they're still wobbly. We say that they're just still learning how to walk. They're earlier on in the timeline of learning, and the only difference between a beginning, intermediate, or expert musician is where they are on that learning time.

So your job when practicing and evaluating your efforts is just to collect data. Data itself is neither good nor bad. It's just data. Also, remember that this kind of evaluation is part of the learning process. What I mean by that is that in addition to the technical components of playing, learning music also requires developing a set of perceptual skills.

So the closer you listen and evaluate, the better those skills will become. Learning anything is really just one grand never-ending science experiment. So approach it with a spirit of curiosity. Approach it knowing that some things you do may work well and others may not. And the goal is really just to collect information on what's working and what isn't.

Need some inspiration to get curious?

See my post from July 2022:

I think that plateaus are frustrating when you are trying too hard to grind it out.

I find them to be puzzles and solving them should be fun.

One thing I’m doing is stretching to learn similar skills on a kick scooter for example scalloping turns to pump and gain momentum was proving a challenge. Yet I found it simpler on the scooter than the bike... once I had it, I was able to apply the skill to slalom drills which let to better bike-body separation, which lead to some success on the bike. Rinse - repeat.

Importantly for me, it was all fun. Playing with the vehicles, exploring potential, exaggerating movement, and trying drills in new venues (riding at night on the parking lot really gets you a different focus) to trigger dopamine and flow.

I was certainly analyzing but being too

much up in my head breaks the process. Talking about it afterwards helped.

Also I enjoyed the podcast!

Cheers.

For me the hard bit with plateaus is believing that there is an 'up' to come. It makes sense that at some point I will inevitably plateau out so maybe I am there already? Approaching the drills with curiosity and fun instead of a focus to acheive will make a difference I think.