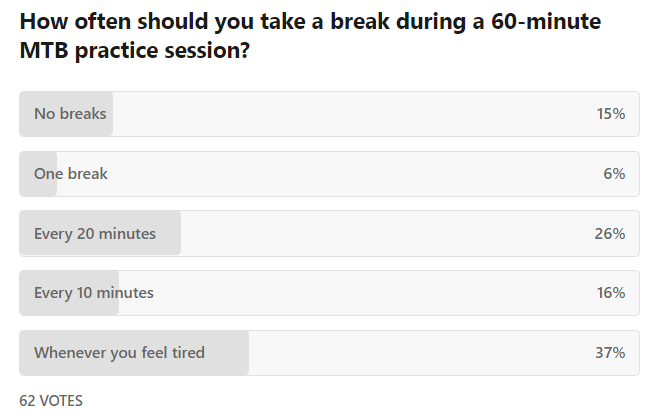

Quiz results: How often should you take a break during a 60-minute MTB practice session?

Results from the August quiz and why your answers were right or wrong

Back in August, I posted a quiz titled:

How often should you take a break during a 60-minute MTB practice session?

Sixty-two people responded. I also asked for people’s thoughts and got substantive responses from Jeff Carpenter, Renee Gregoire, Trevor Kennewell, and Dale Shipman. See their comments and my replies below.

The results of the quiz:

I understand from the research that it's best to take a break after 10 minutes of practice within a broader range of up to 20 minutes. So more than 40% of you were within that range on the quiz.

The science of taking breaks during a practice session (a type of "varied practice") indicates that after an initial period of repetitions from short-term memory, we learn a skill more effectively when we attempt retrieval from long-term memory. And we can't determine that effectiveness until much later—one or more days.

Of course, we’re bummed when the progress we thought we made seems to have evaporated. But our memory of those good feelings compels us to keep using the same tactic, i.e., many repetitions from short-term memory (also known as “massed practice” and “blocked practice”).

What’s the evidence to back this up?

Here are two resources by Peter C. Brown, co-author of the book, Make It Stick — The Science of Successful Learning:

1 - Book excerpt (pages 51-52):

The evidence favoring variable training has been supported by recent neuroimaging studies that suggest that different kinds of practice engage different parts of the brain.

The learning of motor skills from varied practice, which is more cognitively challenging than massed practice, appears to be consolidated in an area of the brain associated with the more difficult process of learning higher-order motor skills.

The learning of motor skills from massed practice, on the other hand, appears to be consolidated in a different area of the brain that is used for learning more cognitively simple and less challenging motor skills.

The inference is that learning gained through the less challenging, massed form of practice is encoded in a simpler or comparatively impoverished representation than the learning gained from the varied and more challenging practice which demands more brain power and encodes the learning in a more flexible representation that can be applied more broadly.

2 - A three-minute video clip from an interview with co-author Peter C. Brown on the 4th Big Idea from the book Make It Stick. “Intuition misleads us. Many strategies that feel productive, like rereading and massed practice, are labor in vain.” (The video clip jumps to the 5:24 mark. Unfortunately, the YouTube preview below shows the interviewer, not Peter Brown.)

Transcript excerpt:

Because you can spend quite a bit of time practicing your 20-foot putt or your four-foot bean bag or your solving of the - finding the volume of a geometric solid, like a spheroid, until you see you've got it nailed.

What you don't understand is that improvement resides in short-term memory. And it hasn't been consolidated in long-term memory. It takes hours or days for learning to be migrated from short-term memory to long-term memory. And you walk off the golf course or leave your classroom with that practice feeling you've got it nailed. Or you spend all-night in an all-nighter and you do well the next day on the exam, you think, “I’ve locked that stuff in.”

If you come back a week later, you haven't. You're astonished to discover it's leaked away in the meantime. So, you cannot trust your sense of what feels productive as a gauge of whether you're truly learning.

From Daniel Coyle in his book, The Little Book of Talent—52 Tips for Improving Your Skills:

Tip #35: Use the 3x10 Technique. Coyle writes:

This piece of advice comes from Dr. Douglas Fields, a neurologist at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, who researches memory and learning.

He discovered that our brains make stronger connections when they’re stimulated three times with a rest period of ten minutes between each stimulation. The real-world translation: To learn something most effectively, practice it three times, with ten-minute breaks between each [set].

“I apply this to learning all the time in my own life, and it works,” Fields says. “For example, in mastering a difficult piece of music on the guitar, I practice, then I do something else for ten minutes, then I practice again [and so on].”

From author Josh Kaufman in his book, The First 20 Hours: How to Learn Anything . . . Fast!

Kaufman writes:

You can also split your practice into several smaller parts, with a short break in the middle if needed: twenty minutes of practice, ten-minute break, twenty minutes of practice, ten-minute break, et cetera.

For motor skills like MTB, a break can take the form of any type of rest or another activity, skill-related or not. My preference is to review the video of that practice set. If I've not captured a video, I like to practice an MTB skill in which I've already achieved a level of proficiency and that's less physically demanding. My current preferences for a skill-related break are track stands and slow fakies.

You were partially right for those of you who selected "Whenever you feel tired" on the quiz. Stop Before You’re Exhausted is Daniel Coyle’s Tip #38. He writes:

In many skills, particularly athletic, medical, and military ones, there’s a long tradition of working until total exhaustion. This tradition has its uses, particularly for improving fitness and mental toughness, and for forging emotional connections within a group.

But when it comes to learning, the science is clear: Exhaustion is the enemy. Fatigue slows brains. It triggers errors, lessens concentration, and leads to shortcuts that create bad habits. It’s no coincidence that most talent hotbeds put a premium on practicing when people are fresh, usually in the morning, if possible. When exhaustion creeps in, it’s time to quit.

It's worth noting that getting momentarily tired from a burst of physical activity is not what I'm talking about. For example, I get temporarily tired from a few bunny hops or a trip around a pump track. But I'm ready to go again after a quick breather. After an hour, however, I'm spent.

My replies to those who commented. (I welcome follow-up comments from anyone.)

Dale Shipman commented:

A break every 10 minutes is needed so you don’t overwork the muscle group you are using

Dale, as I mentioned above, many practice sessions involved bursts of significant exertion for one or more attempts that require some recovery (1-2 minutes?) before we attempt additional reps in a set. And after 10-20 minutes of that, more general fatigue might need a more extended break. But otherwise, a break every 10 minutes is warranted even if you're not working the muscle group hard.

Jeff Carpenter commented:

I think whenever you feel tired, which I'd describe as your body not being able to perform the proper technique. In other words, I'd think you want to maintain the ability to build muscle memory, and not get sloppy, resting as often as it takes. The rests might be as short as a few (say 30) seconds, depending what you're working on.

Jeff, I agree that getting tired, either temporarily after a burst of exertion or more general fatigue after a lengthy session, can negatively affect one’s technique. But rather than thinking that tiredness is about not being able to build muscle memory (a misnomer that I describe here), I think it’s more helpful to think of it as impeding one’s ability to retrieve the maneuver from long-term memory.

Trevor Kennewell commented:

I read one study (can’t remember details) said if you practice a guitar piece nineteen times before getting it right, then stop, having had success, you are practicing the failure nineteen times, and success only once, and therefore what will dominate is the failure.

However, remaining playful does seem to somewhat overrule or ameliorate this response. Perhaps while you can remain focused and playful, in heart and mind, is a good periodicity of practise sessions?

Trevor, remaining focused and playful is always a good combination, but I think it’s often difficult to be playful when you’re new to a skill or stuck at a level for a long time.

Recent research on initially learning a new skill indicates that many failed repetitions are helpful because it cues the brain for neuroplasticity. I’ll have more about this in a future post.

Trevor Kennewell commented:

The science would seem to indicate that you should take a break when you can’t maintain the focus required/desired. To set a time on it is problematic. Current teaching/learning science, from what I have read/understood, perhaps suggests a break every 15-20 minutes will give good development for the broad middle section of the bell curve on a graph of exercise physiology development. What does science actually show us?

Trevor, the ability to maintain focus is indeed huge. I've started work on a long post about developing the skill of concentration. But if we only retrieve repetitions from short-term memory, the benefits are limited no matter how focused we are. Plus, for most recreational athletes, our minds tend to wander more quickly when we keep doing the same thing over and over.

Renee Gregoire commented:

Whenever you feel tired OR getting too quickly frustrated! and I remember from my years of riding horses that if you get some thing right you don’t necessarily have to continue getting it right repeatedly! In other words don’t practice something to the point that you then start over analyzing what you are doing

Renee, see my comments above about getting tired.

I'm glad you mentioned getting frustrated. That is a sign to take a break, for sure! However, I'd argue that taking a break will only ease your frustration if you can change your mindset. I'll have more about mindset in a future post.

Getting a skill right the first time is an important event, but you're right; it's unrealistic to expect that you should be able to get it right after that repeatedly. However, there's a relevant saying: "Practice begins when you get it right." More to come about that!

My comprehensive comment has just been munched, so here's a brief summary:

You seem to be taking an Outside to Inside approach: you are consulting the experts, then conforming to them.

I prefer to define my own, unique, needs -- and then

peruse expert suggestions for possible useful tips.

My practice structure fits around trails and riding..........and THAT dictates resting.

"Long Term Memory" is the next ride.

"Short Term Memory" is the skill actually being used.

My "practice sessions" are usually short periods of time that become available.........tho I do have a custom jump line in my garden.

Some of my other comments were about motivation.

Going from this, maybe different, paradigm, I would therefore choose: "rest whenever it seemed indicated.".........dictated by the circumstances of the activity.